Uncovering Scotland's Whaling Past

C Jenkins 1921

Dr Conor Ryan - HWDT alumni now Science Committee member - has published an incredibly interesting paper on the historical occurrence of whales in Scottish waters. By utilising old whaling records, Conor and his colleagues begin to shed some light on the species which used to inhabit our waters and what we might expect to see if our seas recover from past exploitation.

Growing up in Ireland, it was not unusual to see fin and humpback whales from shore. The reason I bought my first moped was to drive to headlands to watch them. Once, while rock-climbing the sea cliffs of East Cork, I was told-off by my climbing buddy for not paying enough attention when belaying him, because I was so distracted by fin whales pacing up and down along the coast, close enough to hear their blowing. Having searched and searched for large baleen whales since I arrived in the Hebrides eight years ago, my first ever sighting was this September (rather aptly, the whale was previously recorded near my childhood home off Cork!). Given the recent streak of sightings of humpback and fin whales inshore around Scotland, a pertinent question is: are they recolonising our seas? One way to answer this is to look back.

A silver-lining of lockdown was the time to delve into a project that I have daydreamed about for years. I began digging through old whaling records, documented by whalers, to find out where larger whales used to occur in our waters. With support from the Scottish Association of Marine Science (SAMS) in Oban and in collaboration with colleagues at the International Whaling Commission (IWC), we started to build a picture of the distribution and diversity of whales around the Hebrides and Shetland over a century ago. Unfortunately, each record represented a whale that was harpooned. Nonetheless, because we know the date, species, location, length and sex of the whales landed at Scotland’s five whaling stations (four in Shetland and one in Harris), we can learn more about where whales ought to be found, assuming their populations can recover.

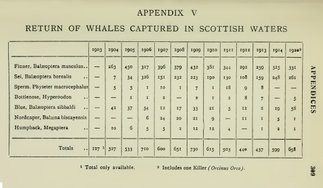

Catch Summary

Findings are as fascinating as they are depressing. We don’t know exactly how many whales were killed here, but our new dataset is an absolute minimum estimate. It contains information about what roamed our seas from 1904 – 1951 and precisely where and when. After weeks of digitising, coding and even translating (thanks Ada Pedersen!), the data emerged gradually, like a painfully slow and horrific Polaroid picture. What started out as a jumble of Norwegian handwritten notes and smudged scans of archived logbooks is now a window into the past (I never thought I’d get this excited about history, but here we are!). The last attempt to estimate how many whales were killed in Scottish waters was by Sidney Brown in 1976: a total of 9,638 whales, but without the catch locations. My research has revealed that this was an underestimate, by a few hundred whales (a 25% underestimate in the case of blue whales: a total of 501 were landed).

A Sei whale - the second most frequently caught species of whale in the Scottish whaling stations - breaks the surface in the waters off Chile. Is this a sight we can expect to see more of in the Hebrides?

Part of the difficulty in understanding the scale of whaling here is that it was mostly carried out by Norwegian whalers and so much of the literature is in Norwegian. Much like the salmon farming industry today, modern whaling was an industry exported out of Norway in response to more restrictive environmental policies there (after decades of over-exploiting whales in Northern Norway). They had the expertise and the vessels. Even “British” whaling companies used Norwegian vessels and crew.

Aside from the sheer scale of the whaling operations, I was astonished to discover how many right whales once occurred in the Hebrides. Right whales may effectively be extinct on this side of the North Atlantic and are in peril on western side, with fewer than 100 breeding females left. Just seven records exist of this species in British and Irish waters since the 1920s - most likely wanderers from the relict western North Atlantic population. By 1906 Norwegian whalers had considered right whales to be “extremely rare and virtually extinct” in Europe. Translated Norwegian texts show how surprised they were to find right whales in the Hebrides in the early 1900s. There was no holding back.

The majority of right whales landed in Scotland were caught to the west and south of the Outer Hebrides, where they were hunted closer to land than any other species, in an arc from St. Kilda to Tiree. Eight individuals were hunted less than 100 km from the whaling station at Bunavoneader, Isle of Harris. The biggest daily catch total was 6 right whales, while 23 individuals were killed during the month of June 1909. To document these landings is, in all likelihood, to document their extinction in the eastern North Atlantic. It seems that Hebrides, may have been their final stronghold. Incredibly, the waters just a few miles west of St. Kilda was historically a regular haunt for blue whales. The last time blue whales were harpooned here was 9 July 1951, when two females measuring 66 and 80 foot long were winched ashore at Bunavoneader. The number of sei whales killed surprised myself and my colleagues - the second most frequently caught species after fin whales. Some were killed within 20 miles of the stations. Do they still occur here today? I hope so.

Before clear ecological inferences can be drawn from these data (e.g., migration patterns and habitat-use), we must better understand the whale fishery itself. How did whalers search for whales? How many were struck-and-lost? Was there under-reporting of catches? Interesting politics were at play at the time, with politicians in Shetland vehemently opposed to whaling by the 1920s (under pressure from objecting herring fishers) while an MP from the Outer Hebrides was supportive. This saw the continuation of whaling in the Hebrides into the 1950s while in Shetland it ceased in 1928.

To finish a rather depressing subject matter on a positive note – recent studies have detected fin, sei, sperm, humpback and bottlenose whales in the deeper waters to the west of Scotland. The COMPASS project is a herculean effort by Denise Risch from SAMS and her colleagues, to monitor whales in the former whaling grounds using sound. An array of hydrophones was fixed to the seabed for months and THIS PAPER was published recently. It’s encouraging that some of the species that the whalers were so familiar with were detected – including singing humpbacks.

Does a recent increase in sightings inshore signify that whales are finally recovering, 70 years after whaling here stopped? It is too early to tell, I think and I would be cautious about speculating. In this regard, a recent study on the critically endangered North Atlantic right whales serves as a warning. Researchers in Boston found that a range-shift in right whales led to a local increase in whale presence over time, despite the clear downward trend in population size. This underscores the importance of long-term and effort-related surveys for detecting changes in cetacean densities, such as those carried out on HWDT vessel Silurian.